Milk costing more than $9 and a tin of instant coffee for an astounding $84. These are real prices – and they show just how dire things are for some Aussie shoppers.

Consumers all across the country are being hit by the cost-of-living crisis, which has sent the price of everyday goods such as lettuce and milk soaring.

But shocking photos shared to social media show how grocery bills cost more in some places – and expose just how dire the situation has become.

Watch the latest News on Channel 7 or stream for free on 7plus >>

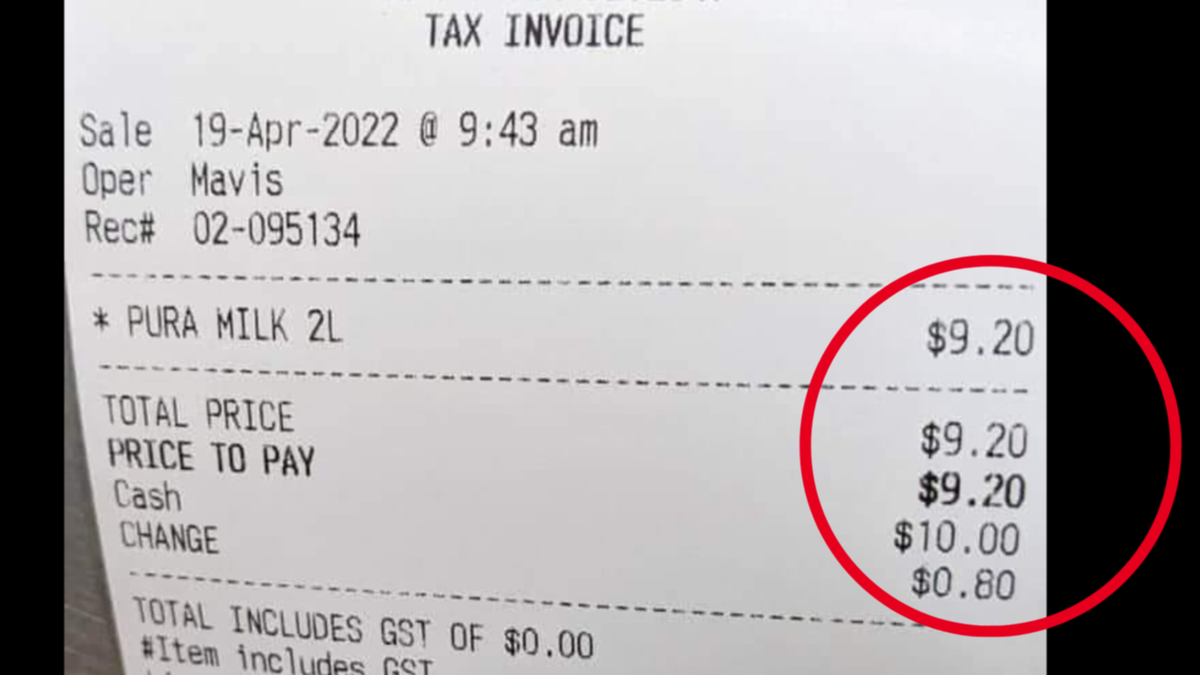

One photo of an April receipt from a store in the town of Kaltukatjara, southwest of Alice Springs, showed a two liter carton of milk costing $9.20.

At a Sydney Woolworths, the same product was being sold for just $3.10 this week.

Donna Donzow, an operations manager for the non-profit EON Foundation which helps grow and supply fresh produce to communities in Western Australia and the Northern Territory, said she noticed the unusually high grocery prices in June when she was in Minyerri, a town 240km southeast of Katherine.

“The cost of a mixed salad pack was $17,” Donzow told 7NEWS.com.au.

By comparison, a mixed bag of salad at a Sydney Woolworths this week cost just $3.

The high grocery prices in remote areas are due to a range of issues including long supply chains, poor quality roads and freight costs – and experts say more needs to be done to sort out the problem.

A long-time problem

Food has cost more in the regions than in our biggest cities for years – as photos on social media show.

One photo shared in 2020 showed a tin of instant coffee selling at a Hope Vale grocery store, in remote Queensland, for $84, according to the poster.

According to a 2021 report by healthcare policy organization Aboriginal Medical Services Alliance Northern Territory (Amsant), food in supermarkets is 56 per cent more expensive in remote communities than in regional supermarkets.

A 2020 inquiry by federal MP Julian Leeser echoed these findings, stating that “the cost of purchasing food is considerably higher for remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities than for people living in larger population centers in urban and regional Australia”.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics says the cost of groceries has increased by 5.9 per cent across all of Australia’s capital cities since June last year – and there’s reason to believe costs are also going up in rural Australia, where prices were already astronomically high.

In Minyerri, for instance, Donzow said she saw signs around the shop advising community members of that fruit and vegetable costs had gone up due to flooding in Australia’s southern states.

EON Foundation executive chair Caroline de Mori said she’d had a similar experience.

“I heard people complaining the other day about a lettuce for sale in Sydney for $8, but can you imagine what it’s like when you go a few thousand kilometers inland?” de Mori said.

“You end up paying $12 for one brown-headed broccoli.”

‘It’s only getting worse’

The enormous costs aren’t just an issue for getting food on the table now – they have flow-on effects for the future.

De Mori told 7NEWS.com.au that the lack of cheap fruit and vegetables meant some shoppers were turning to processed food.

“By the time it all gets (to remote communities) it’s moldy and not fresh, so it’s not necessarily an option,” she said.

“This means we see astronomically higher disease rates and health issues in these communities, and it’s only getting worse.”

De Mori added some communities only have one store selling essentials for the whole town.

“Because they’ve got the monopoly, they can charge whatever they like and it just seems to be a terrible downwards spiral,” she said.

University of Queensland public health policy professor Amanda Lee told 7NEWS.com.au while experts recommended numerous solutions over the years, little has been done overall.

Lee recommends subsidizing freight costs and preventing supermarkets from marking up fruit and vegetables.

“Unfortunately, while there’s a long list of recommendations from all the inquiries over the past 40 years … there’s been very little collective action to address it.”

.