Thousands of tonnes of earth and debris slid down the hillside, slamming into a four-storey ski club lodge, which then hit the Bimbadeen Staff Lodge.

Eighteen people were killed in the darkness and freezing cold.

Several hours down the road, a 21-year-old radio journalist was fast asleep, after a boozy farewell drinks with co-workers in Canberra.

“I was fast asleep when I got a phone call suggesting I get to Thredbo as soon as possible,” Ben Fordham told nine.com.au.

“I didn’t have any information about why I needed to get there but I was told that there were heaps of emergency services vehicles making their way to Thredbo.”

Having drunk too much to drive, Fordham started a “mad ring around” for someone who could drive. Eventually he and three others packed into a car and made the early morning trip.

A police roadblock was keeping all media out of Thredbo.

But Fordham managed to get in before all other journalists, by telling a police officer he was heading for higher ground for better mobile phone reception.

From there he sprinted into the darkness, to be picked up by a local waiting for him.

“When the sun came up the following morning I was the only journalist who was there who was able to describe what we were seeing,” Fordham said.

“It was surreal because it didn’t look real. It looked like the kind of thing you would see in a movie.

“It just looked like a giant stomped on the side of a mountain. And you could tell that there were chalets and other buildings and vehicles that had all been damaged and dislodged.”

Emergency services were frantically trying to determine how they could start the search for possible survivors without setting off another landslide.

“I think the thing I struggled with the most was the concept that there were people underneath all that rubble,” Fordham said.

“It looked to me like there was no way in the world anyone could survive.”

It was a deeply upsetting experience for a 21-year-old journalist, along with the community and family or friends of the victims.

“It was absolutely terrifying to think that people were fast asleep in the middle of the night, laying next to their loved ones.

“And then God knows what happened next. They must have heard a noise. The ground must have started moving. And the next thing you know their whole lives just slipped away.”

The media were kept at a distance as the excavation took place, but Fordham recalled what he saw through the lens of a camera.

“I remember seeing a body being moved, and it was clear to me that the body was frozen stiff,” he said.

“So there was no way in the world in my mind anyone was going to come out of that alive.”

Later that day, a more senior journalist from 2UE had arrived, and Fordham thought it was time for him to leave.

“I was probably suffering from a bit of trauma, to be honest,” he said.

“God knows what the friends and families involved were going through.”

In a phone call that night, Fordham’s father urged him to stay in Thredbo.

“I said that they’re pulling out frozen bodies. There’s no one alive under there. And I feel like I should go,” Fordham said.

The next morning Fordham woke up early and turned on the local radio station.

A local politician had called in to report noises had been heard underneath the wreckage.

Fordham called Sydney and conveyed the news to the nation.

“My boss called me and said ‘You guys better be right about this’,” he said.

“There’s nothing worse than false hope.

“I remember having this awful, empty feeling about the possibility that the noise under there might have been created by something else.”

When Fordham arrived at the command post, he was told what had happened at 5.37am that morning.

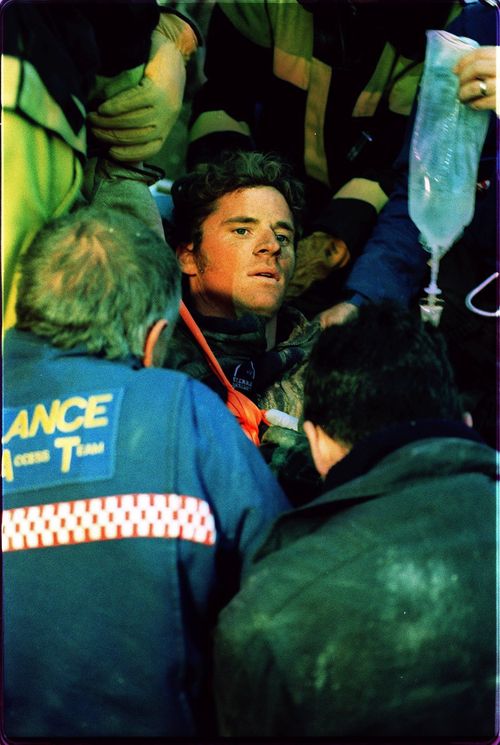

Diver had been uninjured by the landslide, trapped between three concrete slabs.

His wife Sally Diver, who had been sleeping beside him, had been trapped under their bedhead in a depression. As the depression filled with water overnight, she drowned.

Stuart Diver was right beside his wife, but his desperate efforts to save her were unsuccessful.

He spent the next two-and-a-half days under the rubble in his underwear, with freezing water gushing past.

Sixty-five hours after the landslide, Diver was saved, suffering only frostbite.

“We need to remember so many people lost their lives and so many families were heartbroken that day,” Fordham said.

“But I think they would all understand the joy that we all felt when we realized that Stuart was going to get out of there.”

Fordham would go on to win a Walkley Award and a Raward that year for his coverage of the Thredbo landslide – the youngest reporter to do so.

But the impact of covering such devastation stuck with him.

“Months later, I was sitting in the pub in Sydney with some mates and then all of them went off to go and hit the dance floor,” he said.

“I was sitting there on my own and I just started crying.

Hundreds of sharks target shipwrecked sailors

“I think that’s the first time when I allowed myself to comprehend what I’d watched and what I’d experienced because at the time you’re right in the middle of it, you don’t really have that opportunity to sit back and contemplate the whole thing.

“And I was just an observer. So God only knows what it would have been like for the families and friends of those who were involved, let alone for Stuart.”

It was later determined that leaking water mains softening the ground had caused the landslide.