Nothing captures the global media’s attention – and reveals its knack for distracting from the issues of the moment – quite like a good old-fashioned triumph-of-the-human-spirit tale, especially if it involves cute kids being rescued by an international cohort of heroes.

So it was in July 2018, when a Thai junior soccer team was saved from an underground cave by the efforts of local Navy SEALS, volunteers, and British and Australian divers – an operation that dominated news headlines for what seemed like forever.

Filmed in large part on the Gold Coast, Thirteen Lives – directed by Oscar winner Ron Howard (A Beautiful Mind) from a script by Gladiator writer William Nicholson – is the latest and most high-profile of the inevitable screen versions of that event, following the 2019 Thai film The Cave and last year’s National Geographic-produced documentary, The Rescue. (A six-part Netflix drama is due next month; what a time for armchair spelunkers.)

The prolific Howard is nothing if not a steady hand behind the camera, and he certainly has formed in putting collaborative heroism on the screen: in films like the firefighting drama Backdraft, and his tense, gripping space hit Apollo 13, the director’s workmanlike formalism proved to be a perfect match for his subjects.

For Thirteen Lives, Howard appears to be self-consciously shirking Hollywood-style heroics, taking his narrative cues from no fuss – and no frills – news reporting, in which the facts get checked off with minimal dramatic embellishment.

After a short prologue, the film wastes little time in dispatching the teen soccer team (and their 25-year-old assistant coach) to the Tham Luang Nang Non cave where they’ll be trapped by rising floodwaters, rapidly shifting its focus to the burgeoning rescue efforts – and attendant media circus – that spring up in the wake of the boys’ disappearance.

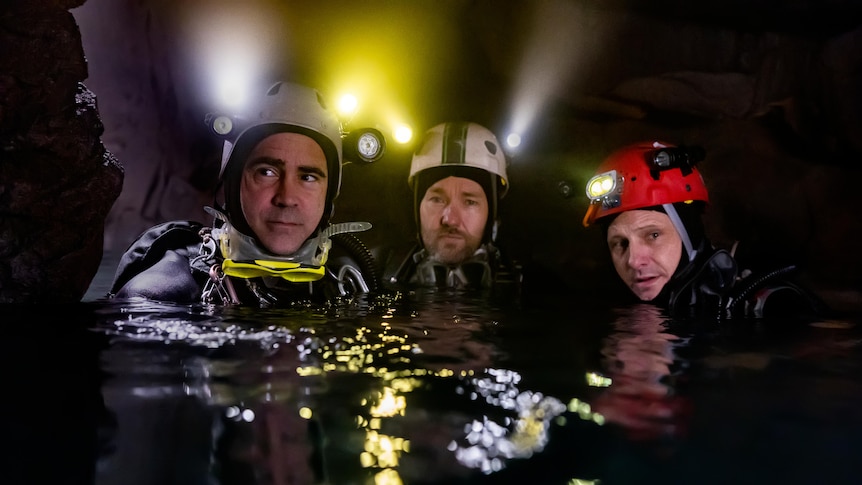

Among the anxious parents, volunteers, besieged former governor and Thai Navy SEALS, Howard zeroes in on two unassuming, middle-aged British volunteer cave divers, Rick Stanton and John Volanthen, respectively played by Viggo Mortensen and Colin Farrell with grim haircuts, dour outfits , and – in Mortensen’s case – a frequently amusing English accent that wouldn’t be out of place on an episode of SNL.

Also joining them is Joel Edgerton, as Australian cave diver and anaesthetist Harry Harris, the man called upon to render the boys unaware ahead of their dangerous – and potentially deadly – journey out of the cave.

“I didn’t come here to kill kids, Rick,” Harris protests, a line of dialogue that yields the movie’s biggest unintentional laugh. “I came here to help you save them.”

With such bare-bones characterization – as cave rescue movies go, it’s not exactly Ace in the Hole – Howard leans into the inherent drama of the situation, following the deliberations on how to extract the boys once they’ve found them. It’s a six-hour-plus dive from the cave where they’re marooned and back to safety, a journey that wends its way through treacherous underwater tunnels that only a skilled diver could possibly navigate.

To his credit, Howard creates a reasonably affective tapestry of anxiety, taking care to give us moments with the boys’ parents, the SEAL team, and the local volunteers attempting to minimize the floodwater breaching the cave.

It’s a measured, unremarkable approach that reflects a modest brand of heroism, one that eschews ego in favor of elevating idealised, collective effort.

Working with gifted cinematographer and longtime Apichatpong Weerasethakul collaborator Sayombhu Mukdeeprom (Memoria), who blends his signature misty exteriors with muddy subterranean work, Howard has gone for an earthy, low-key delivery that’s reluctant – or simply unwilling – to tap into anything in the way of big dramatic moments.

The mode is generic, global humanism; Thirteen Lives would sit comfortably on some world news channel playing as background in an over-lit airport lounge.

But it’s telling that the film’s best moments are its most traditionally crafted, when Howard’s baseball-cap auteurism – his sure grip on action and tightly edited montage – emerges to yield some dizzy, claustrophobic sequences that follow the divers in close proximity as they negotiate the dig tunnels.

When Howard sticks to the action beats, Thirteen Lives is satisfying. But elsewhere, the film’s respectful, risk-averse retelling of real-life events makes for a noticeable lack of lyricism – the kinds of transformational moments that a more adventurous filmmaker might have brought to the table.

No doubt erring toward cultural caution, Nicholson’s screenplay only hints at mystical elements – how, for example, the cave’s guardian “Sleeping Princess” was rumored to be angry with the boys and trapped them in her tears.

The team, meanwhile, goes missing from the first half of the film, effectively reducing them to feel-good ciphers; mascots for global media.

Their absence feels like an oversight; after all, what’s more interesting — a bunch of middle-aged men having strategic rescue conversations or a gang of starved, filthy, likely deranged teenage boys submerged for a week in total darkness?

While Thirteen Lives is perfectly serviceable, one can’t help but wonder if a little Hollywood truth-meddling – a storytelling style that has tragically gone out of fashion – might have given it some of the dramatic flair it needed to really soar.

The film proves that the facts – or at least a dogged adherence to realism – don’t always make for a better movie.

Thirteen Lives is streaming on Prime Video from August 5.

loading

.