A 19-year-old Aboriginal man’s death would likely have been prevented if multiple state authorities had not failed to arrange a life-or-death medical appointment, according to the WA state coroner.

Key points:

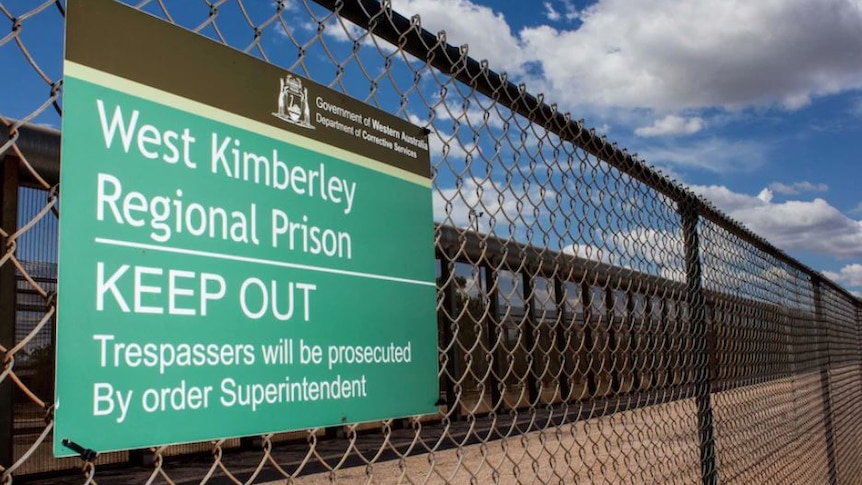

- Mr Yeeda, 19, died of heart failure while in custody at the West Kimberley Regional Prison near Derby in 2018

- He had an ongoing heart problem but a referral for him to see a cardiologist was not followed up on

- The WA coroner says Mr Yeeda’s death was likely preventable but multiple organizations missed opportunities to get him medical help

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised that this story contains an image of a person who has died.

Mr Yeeda, whose first name is being held for cultural reasons, died on May 3, 2018 at the West Kimberley Regional Prison near Derby.

The Miriuwung Gajerrong man was six weeks away from being released when he died from rheumatic heart disease after a game of basketball at the facility.

“He was looking forward to life,” said his mother Marlene Carlton, who released a written statement through the National Justice Project.

“He wanted to do his time so he could come out and live with his dad on a station and work with horses.”

According to the state coroner’s findings released this week, Mr Yeeda had rheumatic heart disease and had a referral to see a cardiologist about getting heart surgery.

However, an appointment for Mr Yeeda was never made.

Surgery likely would have prevented death

Based on an inquest held in September, the WA coroner concluded the young man would likely have been told he needed urgent heart surgery if he had made the appointment.

“If Mr Yeeda had undergone aortic valve replacement surgery, it is likely that his death would have been prevented,” a summary statement from the coroner said.

The coroner added that the WA Country Health Service bore the ultimate responsibility for the referral not being actioned, while the Department of Justice missed an opportunity by not having a computer-based tracking system to make sure urgent prisoner referrals were not missed.

“The WA Country Health Service feels deeply for the deceased’s family,” a spokesperson for the service said.

“While we can never replace their loss, we are working closely with all concerned on the recommendations outlined by the coroner.”

The Department of Justice said it acknowledged the findings of the coroner.

“All deaths in custody are taken seriously and systems and processes will be reviewed in light of the coroner’s recommendations,” the department said in a statement.

WA Cardiology also missed a number of opportunities to assist, according to the coroner.

The service has been contacted for comment.

Coronar’s recommendations

The coroner recommended that the Department of Justice work together with the country health service to improve the exchange of information about the status of referrals, and address tracking system delays created by a lack of resources in the department.

The third and final recommendation was for the department to investigate the feasibility of creating a list that would alert prison officers if an inmate was unfit for sport or work.

Mr Yeeda had been in custody for about one year when he died, having been taken into the facility on May 5, 2017.

He required regular medication and monitoring for heart damage he experienced as a young child, when he had rheumatic fever.

He had surgery for an aortic valve repair when he was a child but it was not a cure for his rheumatic heart disease.

Mr Yeeda was supposed to have monthly penicillin injections but was occasionally resistant to having them.

Arrangements for Mr Yeeda to have heart surgery had previously been made in 2015, but those surgeries were canceled because consent had not been provided by him, or on his behalf.

“However, the fact that there had been no past consent did not mean there would be no future consent,” the coroner wrote.

According to the findings, Mr Yeeda had agreed on December 5, 2017 to see the visiting cardiologist but the appointment was not made.

He died about five months later.

Ms Carlton said her son’s death should have been prevented.

Concerns about racism, lack of cultural care

“There was a lack of communication between the prison and me – if anything happened to him, they should have called me, but they didn’t,” Ms Carlton said.

“There should be a better system to monitor their [the inmates’] health, and they need people in the prison who understand Indigenous culture and health [requirements].”

George Newhouse, the principal solicitor and director of the National Justice Project, said more needed to be done to ensure culturally safe health care in prisons.

“The coroner has failed to address the systemic racism in WA’s justice and healthcare systems which led to Mr Yeeda’s death,” Mr Newhouse said.

Professor Juanita Sherwood, a Wiradjuri woman and board member of the Congress of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Nurses and Midwives, said prison staff should have followed national guidelines for managing rheumatic heart disease.

“These guidelines are easily accessible, and prison and health staff should have known better because we all know it’s a big issue for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities that needs to be managed well,” she said.

“The lack of treatment and follow-through reveal a negligent treatment of Mr Yeeda.”

.