WASHINGTON — Since January, judges in Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana and Ohio have found that Republican legislators illegally drew those states’ congressional maps along racial or partisan lines, or that a trial would very likely conclude that they did. In years past, judges who have reached similar findings have ordered new maps, or had an expert draw them, to ensure that coming elections were fair.

But a shift in election law philosophy at the Supreme Court, combined with a new aggressiveness among Republicans who drew the maps, has upended that model for the elections in November. This time, all four states are using the rejected maps, and questions about their legality for future elections will be hashed out in court later.

The immediate upshot, election experts say, is that Republicans almost certainly will gain more seats in midterm elections at a time when Democrats already are struggling to maintain their bare majority.

David Wasserman, who follows congressional redistricting for the Cook Political Report, said that using rejected maps in the four states, which make up nearly 10 percent of the seats in the House, was likely to hand Republicans five to seven House seats that they otherwise would not have won.

Some election law scholars say they are troubled by the consequences in the long run.

“We’re seeing a revolution in courts’ willingness to allow elections to go forward under illegal or unconstitutional rules,” Richard L. Hasen, a professor at the UCLA School of Law and the director of its Safeguarding Democracy Project, said in an interview . “And that’s creating a situation in which states are getting one free illegal election before they have to change their rules.”

Behind much of the change is the Supreme Court’s embrace of an informal legal doctrine stating that judges should not order changes in election procedures too close to an actual election. In a 2006 case, Purcell v. Gonzalez, the court refused to stop an Arizona voter ID law from taking effect days before an election because that could “result in voter confusion and consequent incentive to remain away from the polls.”

The Purcell principle, as it is called, offers almost no guidance beyond that. But the Supreme Court has significantly broadened its scope in this decade, mostly through rulings on applications that seek emergency relief such as stays of lower court rulings, in which the justices’ reasoning often is cryptic or even unexplained.

Conservatives say the Supreme Court’s wariness of interfering with election preparations is common sense.

“It creates all kinds of logistical issues. Candidates don’t know where they’re running,” said Michael A. Carvin, a lawyer at the firm Jones Day who has handled redistricting cases for Republican clients in a host of states and helped lead the legal team supporting George W. Bush in the 2000 presidential election dispute. Should the original map be upheld later, he said, returning to it would be “triply disruptive to the system.”

The Supreme Court’s Major Decisions This Term

At momentus term. The US Supreme Court issued several major decisions during its latest term, including rulings on abortion, guns and religion. Here’s a look at some of the key cases:

Critics argue, though, that the court is effectively saying that a smoothly run election is more important than a just one. And they note that the longstanding guidance in redistricting cases — from the court’s historic one person, one vote ruling in 1964 — is that using an illegal map in an election should be “the unusual case.”

The Purcell doctrine is not always applied to Republicans’ benefit. In March, the court cited an approaching primary election in refusing to block a North Carolina Supreme Court order undoing a Republican gerrymander of that state’s congressional map.

But scholars say such decisions are the exception. “It just so happens that the unexplained rules in election cases have a remarkable tendency to save Republicans and hurt Democrats,” said Steven I. Vladeck, a University of Texas law professor who addresses the issue in a forthcoming book, “The Shadow Docket. ”

“It would be one thing if the court was giving us a compelling or even plausible explanation,” he added. “But the granting of a stay these days is often done with no explanation at all.”

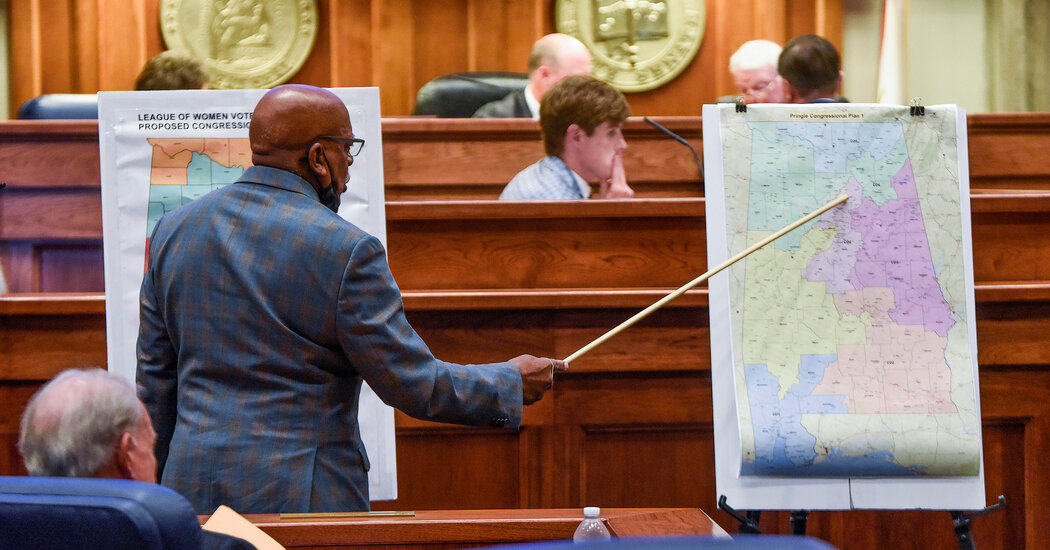

The headline example came in January in Alabama, where a three-judge federal panel said the State Legislature had likely violated the Voting Rights Act by diluting Black voters’ power in its new map of the state’s seven House seats.

The judges ordered the Legislature to draw a new map exactly four months before the May primary elections — a stretch of time that, not long ago, another Supreme Court would have considered generous.

But the Supreme Court issued an emergency stay blocking the order two weeks later, restoring the rejected map for this election. Justice Brett Kavanaugh called the Purcell principle “a bedrock tenet of election law: When an election is close at hand, the rules of the road must be clear and settled.”

In dissent, Justice Elena Kagan shot back: “Alabama is not entitled to keep violating Black Alabamians’ voting rights just because the court’s order came down in the first month of an election year.”

A month later, a federal judge in Georgia cited Mr. Kavanaugh’s words in deciding not to order a new congressional map for that state — this time three months before primary elections — even though he said the State Legislature’s map, like Alabama’s, probably violated the Voting Rights Act.

And in June, the Supreme Court blocked a lower court order for a new congressional map in Louisiana on the same grounds. The justices did not explain their reasoning.

Allowing elections using maps rejected by lower courts has been exceedingly rare in the last half-century. The principal instances occurred after the Supreme Court’s one person, one vote ruling in 1964 forced the redrafting of political maps nationwide.

Politicians have taken notice of the change. In Georgia, the Republican governor, Brian P. Kemp, waited 40 days after the legislature approved a congressional map before signing it into law, leaving a sliver of time for the succeeding court battle.

“The relevant actors are well aware of both Purcell and the court’s inconsistent application of it,” Professor Vladeck said. “So there’s plenty of upside, and very little downside, to try to manipulate the circumstances as much as possible.”

Slow-walking redistricting issues is not confined to federal courts. In Ohio, both congressional and legislative elections this year are being run under maps that the state Supreme Court has ruled are unconstitutional partisan gerrymanders.

The GOP-led Ohio Redistricting Commission, which drew the rejected maps, was threatened with contempt for foot-dragging in producing maps of State Legislature districts. It waited nearly seven weeks this spring to produce a second congressional map after the state Supreme Court rejected the first one.

A three-judge federal panel later imposed the Redistricting Commission’s state legislative maps this spring, citing looming election deadlines. The state Supreme Court again rejected the second congressional map as a partisan gerrymander—but in July, after a long trial, and months after the map had been used in the state’s May primary election.

“What happened in Ohio is an especially egregious flouting of the rule of law, purely for partisan advantage and contrary to what the state’s voters wanted with redistricting reform,” said Ned Foley, an Ohio State University law professor and a leading election law expert. “It’s outright defiance of democracy, and a warning sign for the rest of the nation on how ugly and dangerous this kind of power-grabbing can be.”

Critics say they agree that practical issues matter when elections are imminent. But the Supreme Court “is putting next to no weight on the democratic harms caused by unlawful district maps, while it overstates the administrative inconvenience of redrawing districts,” said Nicholas Stephanopoulos, an election law scholar at Harvard University.

There is, however, one other potential explanation for allowing the use of the rejected maps in November. Some election law experts speculate that the court intends to reverse lower-court decisions striking down the Alabama and Louisiana maps after it hears a crucial election case in October.

The Voting Rights Act clause invoked in those cases, known as Section Two, is used mostly to pursue racial bias in political maps. Mr Carvin, the Jones Day lawyer, said he fully expected the court to take aim at it this term.

“The reality on the ground has changed dramatically” since the act was passed, he said, citing the election of politicians like former President Barack Obama with broad support among white voters. “The Pavlovian requirement that states with a history of racial discrimination need to automatically max out the number of minority-majority districts is no longer the law.”

Critics of the court say it very much is the law, seeing as federal judges in Alabama, Georgia and Louisiana have said so this year. And that is why maps deemed in violation of it should have been replaced, Professor Stephanopoulos said.

But he also said he believed Mr. Carvin’s prediction was probably correct.

.