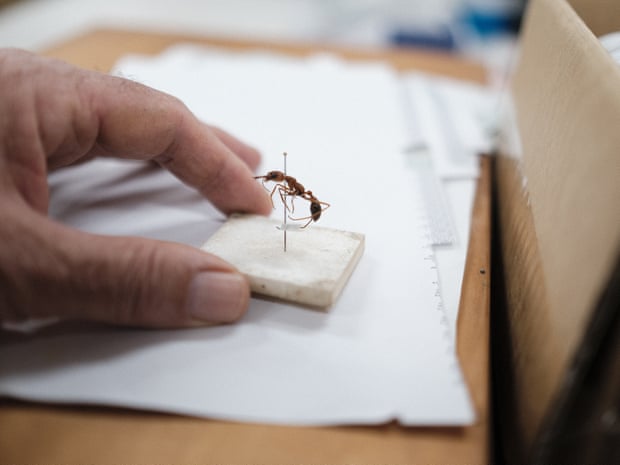

AIan Andersen has been collecting and recording specimens of Australian ant species for 40 years with about 8,000 of them glued to cardboard triangles in a government laboratory in Darwin in the country’s far north.

Each year hundreds of specimens are added to the collection, most of them likely new species that don’t even have formal scientific names.

When insect scientists talk about the world’s hotspot for ant diversity – the place with the highest number of species – they often point to the savannahs of Brazil and the Amazon rainforest.

But Andersen, a professor, ant expert and ecologist at Charles Darwin University, says the true global center for ants is Australia’s monsoonal north, which stretches from the Kimberley in Western Australia to the Northern Territory’s top end and north Queensland in the east.

“Ants are a major part of Australia’s natural heritage,” Andersen says. “We realize what a special place this is for marsupials, and for lizards. And before. We are the kingdom of the ant.”

Andersen’s latest research with colleagues has, he says, added further proof of Australia’s claim to be the global capital for ants.

The research looked at specimens of one group of ants called Monomorium nigrius that has only one species formally described in the scientific literature.

But after genetic analysis of 400 specimens, the scientists estimate there are likely 200 different species in the group just in the monsoonal north of Australia, and another 100 across the rest of the country.

“Ant ecologists will say ant diversity is highest in the Amazon – there can be more than 2,000 species there,” he says. “But here in monsoonal Australia we have at least 5,000.”

Andersen and colleagues wrote that their latest findings were “further evidence that monsoonal Australia should be recognized as a global center of ant diversity.”

‘Unbelievably abundant’

Andersen and his ant-searching colleagues are used to discovering entirely new species in their hundreds.

A few weeks ago, Andersen was walking a path in the Iron Range national park on Queensland’s remote Cape York peninsular with PhD student François Brassard.

One 4mm brownish ant caught his eye. To Andersen, it was clearly a type of last night – an uncommon genus in Australia.

“It had this look about it,” says Andersen, who took it back to his lab. The ant was an Anochetus alae – and only the second time it had ever been found (the first occasion was in Cairns in 1983 and was used years later to formally describe the species).

Andersen has been analyzing specimens collected by colleagues from 100 spots around the Sturt Plateau in the Northern Territory.

The results aren’t published yet, but Andersen says they’ve so far counted about 700 species and about half have never been recorded before.

Brassard is Canadian, and has studied ants in the US and in Macau and Hong Kong. He was skeptical that Australia could top the Amazon for ant species, but not any more.

“In Canada we have about 100 species of ant,” he says. “But we’ll find that many in just a few acres around here. The sheer diversity is unreal. It just seems there’s new stuff everywhere.”

Ants are often collected using pitfall traps – a shallow plastic dish dug a few centimeters into the ground which contain a preservative. Andersen uses ethylene glycol, better known as antifreeze.

His record is 27 species in one 4.5cm wide trap left out for two days in the Northern Territory’s Kakadu national park.

It’s a measure of the sheer numbers of ants in the country.

“People wouldn’t even notice them despite the fact they’re unbelievably abundant around Australia,” he says. “You can have dozens of colonies in an area that’s only 10 by 10 meters.”

Ants play a critical role in ecosystems. They both create and turn over soil, they disperse seeds, some defend plants, and they’re all food for other animals.

If you could weigh all the world’s land-based fauna, Andersen says about 20% of the mass would be taken up by ants.

“They are serious creatures in our environment,” he says They are gun nutrient recyclers. They play an incredibly important role in the flow of energy and nutrients through ecosystems. Ants are down there running the show.”

A 400-year taxonomic challenge

Andersen started collecting ants 40 years ago, and his collection – and those of many others – is housed at CSIRO’s laboratory in Darwin.

Even among these ants – almost all of which are unique to Australia – only 1,500 have been formally named by taxonomists. The collection is one of the largest on the planet.

When scientists such as Andersen use new techniques to discover the true diversity among organisms, it throws up a major challenge for taxonomists – the scientists who painstakingly describe new species and then publish the details in journals.

Prof Andy Austin is the director of Taxonomy Australia. He says hyper-diverse groups of fauna – such as ants – are ushering in a quiet revolution for the profession.

Traditional methods of drafting detailed descriptions, drawings and creating flow-charts, known as keys, to identify one species from another are impractical when new scientific methods offer up thousands and thousands of new candidates.

“You can’t keep doing traditional taxonomy that was developed a hundred or more years ago,” he says.

Austin himself has described about 650 new species – mostly wasps – but it took up most of his 40-year career.

“For Australia, we describe about 1,200 species a year of all organisms. It would take you 400 years to finish all Australia’s biota, and that’s unacceptable for so many reasons.”

He says the new breed of taxonomists are using new techniques, such as describing new species using imaging and genetic data that’s automated. That puts the challenge of describing thousands of new ant species within reach.

“We can’t ask sensible questions about our flora and fauna until we know what’s actually on the continent,” he says.

As the climate changes and land-clearing continues, “there are probably going to be species that go extinct before we get a chance to document them.”