Only a few decades ago the Kaurna language was thought to be extinct.

Key points:

- The first-ever English to Kaurna dictionary is helping to protect the First Nations language from extinction

- South Australia’s Attorney-General says Indigenous languages will play an “increasingly important part” in the state’s education system

- The federal government has pledged $14 million for the teaching of First Nations languages in primary schools

Adelaide’s Kaurna people say it was only ever “sleeping.”

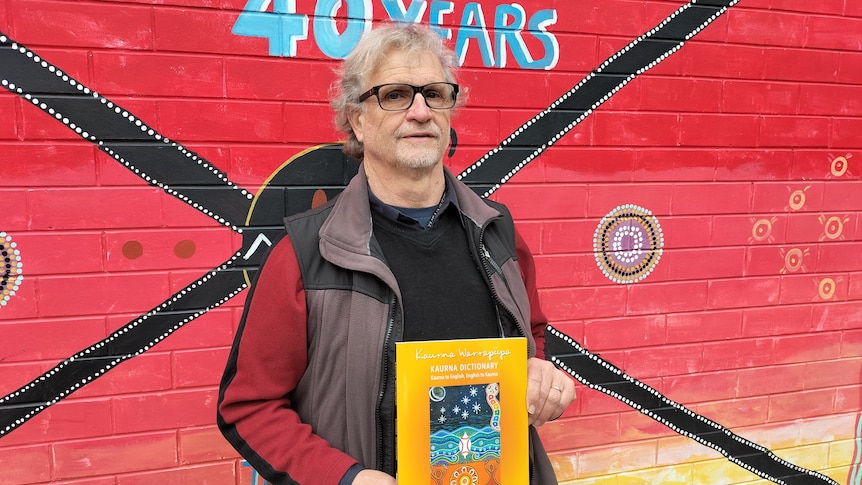

Rob Amery from the University of Adelaide has dedicated his life to reviving Kaurna.

He’s just published the first-ever English to Kaurna dictionary.

“I’m confident that if I got run over by a bus tomorrow it would still continue on,” he said.

“People know enough of the language, know enough of the grammar of Kaurna language to be able to continue the work on without me.”

The Kaurna people’s traditional lands extend from South Australia’s Mid North, through Adelaide, and as far south as the bottom of the Fleurieu Peninsula.

The closest thing to a dictionary before now was written by German missionaries in the 1830s, who documented about 2,000 Kaurna words.

Speaking the language was once forbidden by white Australians, and Kaurna all but faded from use by the 1860s.

Futureproofing First Nations languages

Dr Amery said a physical document was vital for the preservation and growth of the language through education in the community and schools.

His mission, alongside co-authors Susie Greenwood and Jasmin Morley, was to turn a 160-year-old handwritten list of words into a modern handbook for Kaurna.

“We’ve included words from other sources that those German missionaries didn’t record,” he said.

“We’ve done a lot of detailed comparative work with neighboring languages so that we can best work out the optimum pronunciation of those words.”

The dictionary includes 4,000 new words created in consultation with local elders and Kaurna speakers.

For example, mukarntu (computer) comes from a combination of mukamuka (brain) and karntu (lightning).

Until now, school students have learned from a small pool of Kaurna speakers, but several of these have died in recent years.

Charlie Waarruyu Griffiths, who works in secondary education, has been taking part in weekly language sessions at Tauondi Aboriginal College in Port Adelaide.

She said tongue position was the trickiest part to master.

“The Australian-English language is quite a flat tongue, and to do the Kaurna you have to actually put it in different positions and try and make those different sounds, so that’s a little bit hard … there’s definitely some that we get tongue-tied over,” she said.

An ‘increasingly important part’ of education and reconciliation

Dr Amery’s next challenge is training enough speakers who can pass on the language to future generations.

“More than 80 per cent of South Australian schools are in Kaurna country, and they’re desperately looking for teachers of Kaurna,” he said.

“We need 20 times as many people as we’ve got at the moment.”

He wants Australia to take inspiration from New Zealand’s treatment of Māori culture.

“If we look across the Tasman, in New Zealand every schoolteacher has to know some Māori language,” he said.

“It’s become part of New Zealand life, not just Māori life but New Zealand life. I think that’s the way it should be here as well.”

At a federal level, the Albanese government has pledged $14 million to teach First Nations language at 60 primary schools.

Schools can apply to join the program, which is funded for the next three years.

South Australian Attorney-General Kyam Maher is the first Aboriginal person to hold the attorney-general position anywhere in the country.

He said Indigenous languages would play an “increasingly important part” in the state’s education system.

“I know my kids as they’ve gone through primary school in Adelaide have learned about Kaurna culture, but also learned Kaurna words and Kaurna language, and I think we’ll see that increasingly in the future,” he said.

“And that will only help with reconciliation.

“It allows for Aboriginal people to have more pride, reclaiming who they are in a greater and more meaningful way.”

Strengthening identity through language

Katrina Karlapina Power created the artwork for the dictionary’s front cover.

She has been using the revived Kaurna language to bring back traditional birth and death ceremonies.

“As a result of invasion, that language was taken away from us, we were forbidden to speak it, so part of this claim of language is to strengthen identity,” she said.

“This is for Australia and those living in Kaurna country.”

“We need white Australians to get over that fear of first contact and come into our camp and learn our way and our language so this isn’t just a thing for Aboriginal people, for Kaurna people.”

.