The FBI had scarcely decamped from Mar-a-Lago when former President Donald J. Trump’s allies, led by Representative Kevin McCarthy of California, began a bombardment of vitriol and threats against the man they see as a foe and foil: Attorney General Merrick B Garland.

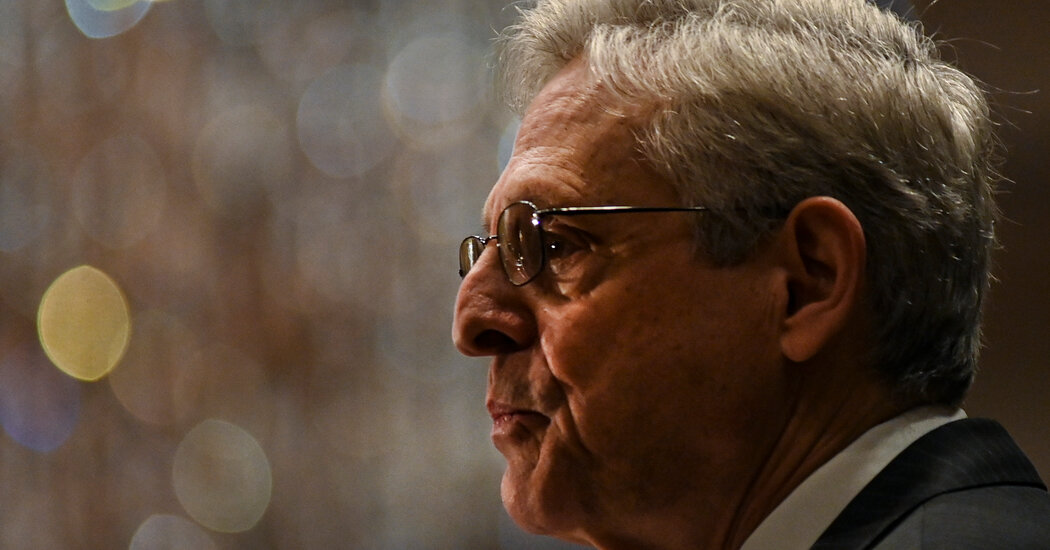

Mr. Garland, a bookish former judge who during his unsuccessful Supreme Court nomination in 2016 told senators that he did not have “a political bone” in his body, responded, as he so often does, by not responding.

The Justice Department would not acknowledge the execution of a search warrant at Mr. Trump’s home on Monday, nor would Mr. Garland’s aides confirm his involvement in the decision or even whether he knew about the search before it was conducted. They declined to comment on every fact brought to their attention. Mr. Garland’s schedule this week is devoid of any public events where he could be questioned by reporters.

Like a captain trying to keep from drifting out of the eye and into the hurricane, Mr. Garland is hoping to navigate the sprawling and multifaceted investigation into the actions of Mr. Trump and his supporters after the 2020 election without compromising the integrity of the prosecution or wrecking his legacy.

Toward that end, the attorney general is operating with a maximum of stealth and a minimum of public comment, a course similar to the one chartered by Robert S. Mueller III, the former special counsel, during his two-year investigation of Mr. Trump’s connections to Russia.

That tight-lipped approach may avoid the pitfalls of the comparatively more public-facing investigations into Mr. Trump and Hillary Clinton during the 2016 election by James B. Comey, the FBI director at the time. But it comes with its own peril — ceding control of the public narrative to Mr. Trump and his allies of him, who are not constrained by law, or even fact, in fighting back.

“Garland has said that he wants his investigation to be apolitical, but nothing he does will stop Trump from distorting the perception of the investigation, given the asymmetrical rules,” said Andrew Weissmann, who was one of Mr. Mueller’s top aides in the special counsel’s office.

“Under Justice Department policy, we were not allowed to take on those criticisms,” Mr. Weissmann added. “Playing by the Justice Department rules sadly but necessarily leaves the playing field open to this abuse.”

Mr. Mueller’s refusal to engage with his critics, or even to defend himself against obvious smears and lies, allowed Mr. Trump to fill the political void with reckless accusations of a witch hunt while the special counsel confined his public statements to dense legal jargon. Mr. Trump’s broadsides helped define the Russia investigation as a partisan attack, despite the fact that Mr. Mueller was a Republican.

Some of the most senior Justice Department officials making the decisions now have deep connections to Mr. Mueller and view Mr. Comey’s willingness to openly discuss his 2016 investigations related to Mrs. Clinton and Mr. Trump as a gross violation of the Justice Manual, the department’s procedural guidebook.

The Mar-a-Lago search warrant was requested by the Justice Department’s national security division, whose head, Matthew G. Olsen, served under Mr. Mueller when he was the FBI director. In 2019, Mr. Olsen expressed astonishment that the publicity-shy Mr. Mueller was even willing to appear at a news conference announcing his decision to lay out Mr. Trump’s conduct but not recommend that he be prosecuted or held accountable for interfering in the Russia investigation.

But people close to Mr. Garland say that while his team respects Mr. Mueller, they have learned from his mistakes. Mr. Garland, despite his silence from him this week, has made a point of talking publicly about the investigation into the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol on many occasions — even if it has only been to explain why he cannot talk publicly about the investigation.

“I understand that this may not be the answer some are looking for,” he said during a speech marking the first anniversary of the Capitol attack. “But we will and we must speak through our work. Anything else jeopardizes the viability of our investigations and the civil liberties of our citizens.”

How Times reporters cover politics.

We rely on our journalists to be independent observers. So while Times staff members may vote, they are not allowed to endorse or campaign for candidates or political causes. This includes participating in marches or rallies in support of a movement or giving money to, or raising money for, any political candidate or election cause.

At the time, that comment was intended to assuage Democrats who wanted him to more aggressively pursue Mr. Trump. Now it is Republican leaders, including Mr. McCarthy, Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky and former Vice President Mike Pence, who are clamoring for a public explanation of his actions.

Mr. Garland enjoys a significant advantage over Mr. Mueller as he heads into battle. The House committee investigating the assault on the Capitol intends to continue its inquiry into the fall, and its members plan to make the issue of Mr. Trump’s actions a central political theme through the midterm elections and into 2024, providing Mr. Garland with the kind of covering fire Mr. Mueller never had.

Still, some of the attorney general’s supporters think he should be doing more to defend himself.

Even though the Justice Department does not generally talk about cases, guidelines preventing prosecutors from publicly discussing criminal investigations include exceptions to the mum-is-the-word norm. Federal prosecutors sometimes explain why they choose not to bring charges in high-profile matters if it is deemed to be in the public interest.

“In this era, does the public interest require more?” said Tali Farhadian Weinstein, a former federal prosecutor, who believes the department can better educate the public on how the rule of law works — without running afoul of laws governing grand jury material and ethical considerations.

“When you have Trump calling this a raid, why not explain how a search warrant works?” she asked. “Could that kind of information come out of the mouth of a public official, rather than a legal analyst on television?”

But Justice Department officials are painfully aware of the risks they are facing in such a politically sensitive inquiry, and many are bracing for the investigations Republicans have explicitly threatened to conduct if they take back the House in November’s elections.

As a result, Mr. Garland’s aides have been wary about disclosing even basic information, including the attorney general’s role in major decisions or the deployment of key personnel like Thomas P. Windom, who was tapped last fall to lead the investigation out of the US attorney’s office in Washington.

The FBI search at Mar-a-Lago appears to have been focused on Mr. Trump’s handling of materials that he took from the White House residence at the end of his presidency, including many pages of classified documents.

For now, there is no indication that the search, which was approved by a federal judge, is related to the department’s widening investigation into the plan to create slates of voters that falsely said Mr. Trump had won in key swing states in 2020.

However, the information gathered by investigators at Mar-a-Lago could be used in other cases if it proves relevant, according to Norman L. Eisen, who served as special counsel to the House Judiciary Committee during Mr. Trump’s first impeachment.

Nonetheless, by late Monday, the former president and his supporters tried to seize the offensive by filling the rhetorical void left by federal investigators, accusing Mr. Garland of perverting justice for political motives.

In the past, Democrats have been relentless in arguing that Mr. Trump’s behavior as president evoked the actions of dictators in other countries. In a statement on Monday night about the Mar-a-Lago search, Mr. Trump repurposed that line of criticism.

“It is prosecutorial misconduct, the weaponization of the Justice System, and an attack by Radical Left Democrats who desperately don’t want me to run for President in 2024,” he said in the statement, adding, “Such an assault could only take place in broken, Third-World Countries.”

As often happens, that argument quickly became a template for his supporters, especially those running for office this year. “The weaponization of Biden’s DOJ against political enemies is unprecedented,” Attorney General Eric Schmitt of Missouri, the Republican nominee for Senate in that state, wrote on Twitter. “This is Banana Republic stuff,” he added.

But no one went quite so far as Mr. McCarthy, the House Republican leader, who has sought to rehabilitate his relationship with the former president after sharply criticizing Mr. Trump’s actions on Jan. 6.

“I’ve seen enough,” Mr McCarthy said. “The Department of Justice has reached an intolerable state of weaponized politicization. When Republicans take back the House, we will conduct immediate oversight of this department, follow the facts, and leave no stone unturned.”

A Justice Department spokeswoman had no comment.