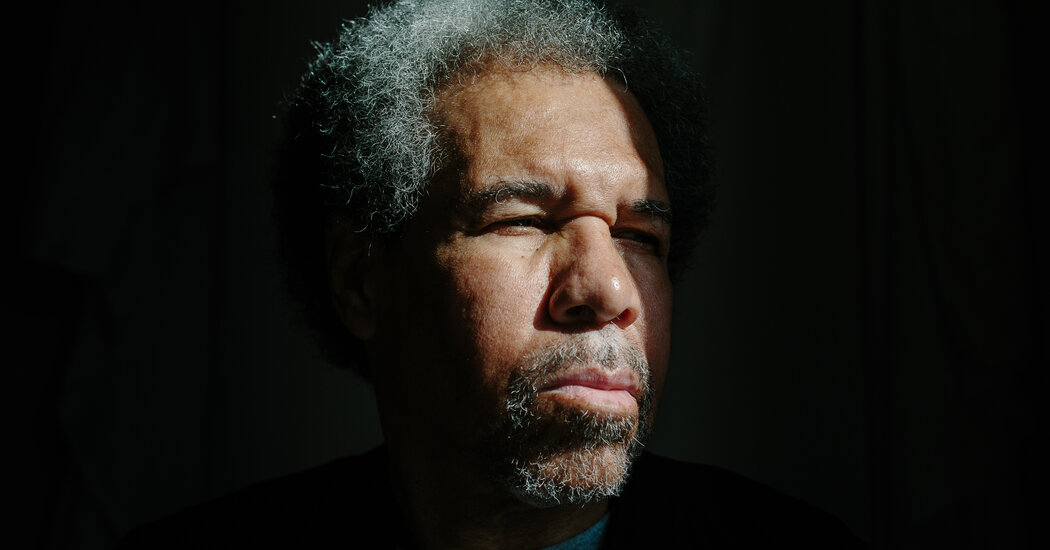

Albert Woodfox, who spent 42 years in solitary confinement — possibly more time than any other prisoner in all of American history — yet emerged to win acclaim with a memoir that declared his spirit unbroken, died on Thursday in New Orleans. He was 75.

His lead lawyer, George Kendall, said the cause was Covid-19. Mr. Kendall added that Mr. Woodfox also had a number of pre-existing organ conditions.

Mr. Woodfox was placed in solitary confinement in 1972 after being accused of murdering Brent Miller, a 23-year-old corrections officer. A tangled legal order ensued, including two convictions, both overturned, and three indictments stretching over four decades.

The case struck most commentators as problematic. No forensic evidence linked Mr. Woodfox to the crime, so the authorities’ argument depended on witnesses, who over time were discredited or proved unreliable.

“The facts of the case were on his side,” The New York Times editorial board wrote in a 2014 opinion piece about Mr. Woodfox.

But Louisiana’s attorney general, Buddy Caldwell, saw things differently. “This is the most dangerous person on the planet,” he told NPR in 2008.

Mr. Woodfox’s punishment defied imagination, not only for its monotony — he was alone 23 hours a day in a six-by-nine-foot cell — but also for its agonies and humiliations. He was gassed and beaten, he wrote in a memoir, “Solitary” (2019), in which he described how he had kept his sanity, and dignity of him, while locked up alone. He was strip-searched with needless, brutal frequency.

His plight first received national attention when he became known as one of the “Angola Three,” men held continuously in solitary confinement for decades at the Louisiana State Penitentiary, which is commonly called Angola, after a slave plantation that once occupied the site.

In 2005, a federal judge wrote that the length of time the men had spent in solitary confinement went “so far beyond the pale” that there seemed not to be “anything even remotely comparable in the annals of American jurisprudence.”

Mr. Woodfox would spend more than another decade in solitary before becoming, in 2016, the last of the three men to be released from prison.

His first stint at Angola came in 1965, after he was convicted of a series of minor crimes committed as a teenager. The prison was notoriously harsh, even to the point of conjuring the days of slavery. Black, like Mr. Woodfox, did field work by hand, overseen by white prison guards on horseback prisoners, shotguns across their laps. New inmates were often induced into a regime of sexual slavery that was encouraged by guards.

Released after eight months, he was soon charged with car theft, leading to another eight months at Angola. After that, he embarked on a darker criminal career, beating and robbing people.

In 1969, Mr. Woodfox was convicted again, this time for armed robbery, and sentenced to 50 years. By then a seasoned lawbreaker, he managed to sneak a gun into the courthouse where he was being sentenced and escaped. I have fled to New York City, landing in Harlem.

A few months later he was incarcerated again, this time in the Tombs, the Manhattan jail, where he spent about a year and a half.

It proved to be a turning point, he wrote in his memoir. At the Tombs, he met members of the Black Panther Party, who governed his tier of cells not by force but by sharing food. They held discussions, treating people respectfully and intelligently, he wrote. They argued that racism was an institutional phenomenon, infecting police departments, banks, universities and juries.

“It was as if a light went on in a room inside me that I hadn’t known existed,” Mr. Woodfox wrote. “I had morals, principles and values I never had before.”

I added, “I would never be a criminal again.”

He was sent back to Angola in 1971 thinking himself a reformed man. But his most serious criminal conviction — for murdering the Angola corrections officer in 1972, which he denied — still lay ahead of him, and with it four decades in solitary, a term broken for only about a year and a half in the 1990s while he awaited retrial.

The other two members of the Angola Three, Robert King and Herman Wallace, were also Panthers and began their solitary confinement at Angola the same year as Mr. Woodfox. The three became friends by shouting to one another from their cells. They were “our own means of inspiration to one another,” Mr. Woodfox wrote. In his spare time, he added, “I turned my cell into a university, a hall of debate, a law school.”

He taught one inmate how to read, he said, by instructing him in how to sound out words in a dictionary. He told him to shout to him at any hour of the day or night if he could not understand something.

Albert Woodfox was born on Feb. 19, 1947, in New Orleans to Ruby Edwards, who was 17. He never had a relationship with his biological father, Leroy Woodfox, he wrote, but for much of his childhood he considered a man who later married his mother, a Navy chef named James B. Mable, his “daddy.”

When Albert was 11, Mr. Mable retired from the Navy and the family moved to La Grange, NC Mr. Mable, Mr. Woodfox recalled, began drinking and beating Ms. Edwards. She fled the family home with Albert and two of his brothers from him, taking them back to New Orleans.

As a boy, Albert shoplifted bread and canned goods when there was no food in the house. He dropped out of school in the 10th grade. His mother tended bar and occasionally worked as a prostitute, and Albert grew to loathe her.

“I allowed myself to believe that the strongest, most beautiful and most powerful woman in my life didn’t matter,” he wrote in his memoir.

His mother died in 1994, while he was in prison. He was not allowed to attend her funeral.

The first of the Angola Three to be let out of prison was Mr. King, whose conviction was overturned in 2001. The second, Mr. Wallace, was freed in 2013 because he had liver cancer. He died three days later.

In a deal with prosecutors, Mr. Woodfox was released in 2016 in exchange for pleading no contest to a manslaughter charge in the 1972 killing. By then he had been transferred out of Angola.

His incarceration over, the first thing he wanted to do was visit his mother’s grave.

“I told her that I was free now and I loved her,” he wrote. “It was more painful than anything I experienced in prison.”

Mr. Woodfox is survived by his brothers, James, Haywood, Michael and Donald Mable; a daughter, Brenda Poole, from a relationship he had in his teenage years; three grandchildren; four great-grandchildren; and his life partner of him, Leslie George.

Ms. George was a journalist who began reporting on Mr. Woodfox’s case in 1998 and met him in 1999. They became a couple when he was released from prison.

Ms. George co-wrote Mr. Woodfox’s book, which was a finalist for the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize in nonfiction. In a review in The Times, Dwight Garner called “Solitary” “uncommonly powerful”; in The Times Book Review, the writer Thomas Chatterton Williams described it as “above mere advocacy or even memoir,” belonging more “in the realm of stoic philosophy.”

After being released, Mr. Woodfox had to relearn how to walk down stairs, how to walk without leg irons, how to sit without being shackled. But in an interview with The Times right after his release from him, he spoke of having already freed himself years earlier.

“When I began to understand who I was, I considered myself free,” he said. “No matter how much concrete they use to hold me in a particular place, they couldn’t stop my mind.”