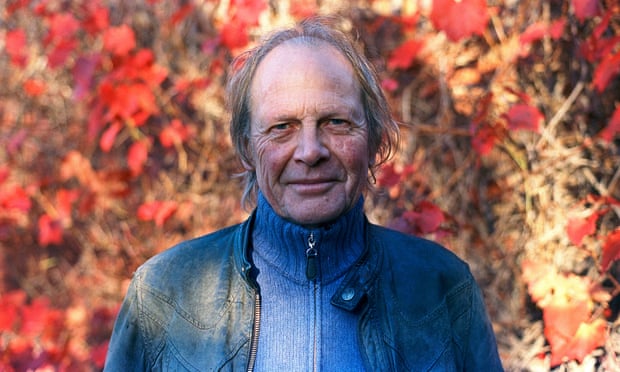

The first photo Richard Crawley ever took was a family portrait, when he was only a boy: a blurry black-and-white picture of his parents and siblings, frozen in time. It’s the kind of forgettable photo others might throw out, but for Crawley, now 71, it was the beginning of the rest of his life.

Over the following decades, he has captured about 400 hours of footage of everything that made up his life in Victoria, Australia – house moves, holidays, school pickups, pets, renovations. His main subjects were his wife Carol (who “tolerated” the filming) and his son James. Sometimes his inspirations from him were odd. “There’s the cutlery!” he proclaims, yanking open the drawer, in a moment of surviving footage. Or: “I’m just going to video these tomatoes,” he says seriously, zooming in on a very ordinary basket of tomatoes. He captured baby James eating an orange for a whole hour. Whatever his reason for it, he never did anything with the film.

But James, now 34, did: premiering at Melbourne film festival this month, his documentary Volcano Man was a way to better understand Richard who, in a time of great tragedy, the father was not needed.

Richard’s impulse to film things, James observes in the documentary, is “less for his family and more for him – its the same reason someone writes their name on a bathroom wall: I’m here, I exist, I did this.” Richard, on the other hand, views his habit of him as a “celebration of this extraordinary thing we call life.” When the three of us meet, he gives us both various explanations involving photography and Diane Arbus and cinéma vérité.

“And that’s why I filmed you eating an orange for an hour,” he finishes, addressing James. “It went on for an hour, so I filmed for an hour!”

“I still don’t get it,” James says.

In Volcano Man, father and son step uneasily around each other in their new roles as subject and director. “The first 30 seconds are critical – but then again, I’m not the director, am I?” Richard says during his introduction to him, a little prickly. He is the dream subject: a kind-hearted, gregarious, frustrating, often arrogant man; a former photographer who loves taekwondo, rock music and his red Ferrari from him. He possesses an unrivaled optimism – his much-repeated mantra of him is “onwards and upwards” – and an unwavering self-belief that amazes and sometimes irritates his son, who sees behind the embellishments and bravado.

How does Richard feel, that his son made the film instead of him? “I love no one more than Jamie – he’s my son, but he’s also my best friend in lots of ways. And so when you’ve got that kind of relationship, there’s a lot of trust involved… I’m delighted that the film has been made, even if it’s not by me.” I have chuckles.

“I said to James, you can use anything you like, no holds barred. There’s no bullshit here.” I have paused. “I think I’ve been quite courageous, actually. So have James.”

Richard wasn’t always the dream father. When Carol died at the age of 52 from cancer, James felt his father’s relentless optimism had disguised how sick Carol had been in the lead-up, denying him more time to say goodbye. “Just like that, mum was gone. He kept saying how she wouldn’t want us to feel bad,” he says, in Volcano Man. “But all I wanted to do was feel bad, with him.”

Meanwhile, alone in his house in Tower Hill – built on the rim of a dormant volcano – Richard began documenting his loneliness and grief. “I’m just really lonely,” he weeps in one clip; in another, he rages at the “incoherent, indulgent bullshit” he is making. “Who is going to want to see this?” he pleads to the camera.

James knew his father had filmed his grieving process but hadn’t wanted to watch it. “I was busy enough trying to work out the grief thing myself,” he says. But in Christmas 2020, James watched the 30-hours of footage by himself, “which was pretty harrowing. It’s pretty full on, very raw.”

But both men knew there was the makings of something great in there, so James went back and watched the rest of Richard’s footage, including the exact moment James burst into the world, squalling in the doctor’s arms.

“With something so close, you can’t see the forest for the trees. I watch the film now and see my life. I’m amazed people think it’s good. It’s just stuff to me,” James says. “I was most terrified about making something that meant something to me and Dad and no one else. How do you make the specific universal?”

“It’s easy,” Richard interjects. “You make your dad seem a bit unhinged.”

“Well,” James says. “Everyone gets frustrated with their parents. And your greatest strength, Dad, is also your greatest frustration for your son, which is your attitude – which is an amazing attitude and very unique and incredibly optimistic and a wonderful way to live.”

At its heart, Volcano Man is about two men grieving in identical and utterly different ways. While they don’t always understand each other, they come to a point where they can finally have a conversation about her death. “It took me years, and a film, to be able to talk about the things that I needed to talk about,” James says. “But I wouldn’t change any of it. It was the right thing to do at the time. Being emotionally available is very important. You’re never gonna get clarity on all of it or work it all out – but if you don’t try, then what’s the point?”

“Exactly,” says Richard. “That’s why we’re here!”

The film is dedicated to “all the mums, especially Carol”. It’s hard not to feel envious, at times, that both men have such a complete record of their loved one – perhaps incidental in Richard’s quest to make his mark on the world, as James says, but as Richard would put it, it is still a celebration of Carol.

“It is amazing to bring her back, in a way, in this film – it has been lovely for me,” says James. “And a catharsis for sure. It’s a goodbye that I didn’t get to say the way I wanted to. But now I can. And we wouldn’t have done it at all, if you hadn’t filmed everything, Dad.”

“One thing leads to another,” Richard says. “To have this out there, I’m really pleased. And the fact James has done it – great! Mission accomplished.” You did the hard work, I say, and he laughs: “James had the easy bit!”